I believe in humanity. We are an incredible species. We're still just a child creature, we're still being nasty to each other. And all children go through those phases. We're growing up, we're moving into adolescence now. When we grow up - man, we're going to be something!

This week everybody was talking about scandals and pseudo-scandals

As the week went on, though, the scandals mostly fell apart -- particularly after it came out that Republicans had faked the "White House emails" that led to ABC's big scoop.

I summarize the current state of the Benghazi, IRS, and AP stories -- and explain why Republicans feel compelled to manufacture these pseudo-scandals -- in Blow Smoke, Yell Fire.

Oh, and I forgot to cover UmbrellaGate.

and Angelina Jolie

If you'd told me last week that Angelina Jolie's breasts would be front-page news, I'd have pictured a very different scenario. But Tuesday she announced in the New York Times that she had chosen to have a preventive double mastectomy, replacing both of her (apparently healthy) breasts with implants to reduce her risk of breast cancer.

Jolie's situation is unusual: Her mother died of ovarian cancer at 56, and genetic tests showed a defective BRCA1 gene that is associated with high risk of both breast cancer and ovarian cancer. Still, her decision was a Rorschach test that produced strong reactions of all types, especially among women. (A good collection of links is here.)

Many were strongly supportive and appreciated the fact that Jolie had put a public face on a difficult issue. I was reminded of Magic Johnson's announcement in 1991 that he had HIV. It's easy to either ignore a medical problem or demonize the people who have it, until it hits someone you know. Celebrities play the role of someone-you-know for an entire society.

Some people reacted negatively. For people who are generally suspicious of the medical establishment, Jolie's story is a Minority-Report-style nightmare, where drastic actions are taken based on predictions whose accuracy is unknowable. M.D. Daniela Drake describes her own experience.

Now I know why patients are so mad at us. This is supposed to be patient-centered care. But it feels more like system-centered care: the medical equivalent of a car wash. I’m told incomplete and inaccurate information to shuttle me toward surgery; and I’m not being listened to.

I came to discuss nutrition, exercise and close follow-up.

I’m told to get my breasts removed—the sooner the better.

The other issue this cast a light on is gene patents: Even if you think you might be in Jolie's situation, getting the genetic test will probably cost about $3000, and insurance often doesn't cover it. Why is it so expensive? Because Myriad Genetics "owns" the BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes. It doesn't just own the testing procedure; it has a patent on the genes themselves. Even a company that came up with a different test couldn't market it. If that seems weird, that's probably because it is weird. The Supreme Court is supposed to hear a case about that soon, though it's hard to imagine the Roberts Court ruling against any form of property.

[Full disclosure: My wife is a breast cancer survivor whose mother died of breast cancer. She recently had the same genetic test as Jolie, which our insurance covered. If it had come out badly -- it didn't -- she would have faced a similar choice.]

and the new Star Trek movie

OK, maybe my definition of "everybody" is skewed. Still, lots of people who ordinarily write about other things were writing about Into Darkness, the second step in the J. J. Abrams reboot of the Trek movie franchise. I haven't seen it yet, but the reactions from people who have center on two themes:

- It's a fine futuristic action flick, beautifully filmed, with great effects, etc.

- Star Trek should be more than that.

It's interesting that the serious-fan discontent is coalescing around Abrams' second film, but I think I know why: For the first, fans were just glad the reboot was happening. They/we wanted the original characters back, but the original actors were too old to carry on. Plus, the reboot's plot necessarily was about how to get the band back together without trapping them in a narrative universe where all possible suspense is killed by what we already know about the Federation's future. Mission accomplished well enough to justify a new series of movies. Fine.

But the second movie has to answer the question: What are you going to do with the freedom the new timeline grants? All the challenges faced in the old timeline -- Klingons, Romulans, Q, the Borg, the Ferengi, etc. -- are still out there somewhere. That invites a long background meditation on fate: What has to turn out the way it did the first time, and what could change? Or we could forget all that and have a lot of starship chase scenes and shoot-outs with phasers.

Which raises the question: What is Star Trek about, really?Matt Yglesias (who usually doesn't write about this kind of thing) sees the heart of the franchise in the optimistic liberal values of the mid-20th century: envisioning a future where humanity gets past its tribal struggles, overcomes scarcity, and devotes its most powerful starship to seeking knowledge and helping other species rather than aggrandizing its wealth and power. Star Trek celebrates the kind of courage you need to hang in an uncertain situation and not shoot, while waiting for a peaceful solution to emerge.

Bad Astronomy's Phil Plait sums up:

At its best [Star Trek] was a deeply thoughtful mythology about ourselves and our conflicts, an allegory of our modern problems and flaws of humanity—war, greed, bigotry, narcissism—and how we overcome them, told as science fiction. That’s why we’re still telling these stories nearly 50 years later.

This movie wasn’t any of that.

NYT's A. O. Scott seems to agree:

it’s hard to emerge from “Into Darkness” without a feeling of disappointment, even betrayal. Maybe it is too late to lament the militarization of “Star Trek,” but in his pursuit of blockbuster currency, Mr. Abrams has sacrificed a lot of its idiosyncrasy and, worse, the large-spirited humanism that sustained it.Atlantic's Christopher Orr sees the surrender of Star Trek's "deliberative, technology-obsessed, and science fictive" values to "visceral, imbued with mysticism, and space operatic" Star Wars values. (Abrams is the current custodian of both movie franchises.)

Salon's Andrew O'Hehir recalls Abrams complaining that previous Star Treks were "too philosophical" and accounts for Into Darkness like this:

the Abrams “Star Trek” movies feel as if they didn’t just depict an alternate universe but were created in one – a universe in which the original “Star Trek” was an action-adventure Marvel Comics title rather than a geeky, Enlightenment-saturated 1960s TV series. ... There’s absolutely nothing wrong with “Star Trek Into Darkness” – once you understand it as a generic comic-book-style summer flick faintly inspired by some half-forgotten boomer culture thing.

He fantasizes "that those in charge of the 'Star Trek' universe could have entrusted its rebirth to someone who actually liked it."

But hey, Into Darkness will probably make money, and that's what counts. I think the Ferengi have a rule about that.

and you also might be interested in ...

If Europe is proving that austerity economics doesn't work, Japan is an interesting test case in the opposite direction. The Abe government has decided to stimulate its way out of the country's decades-long funk, debt be damned.

Japan's national debt is approaching 245% of GDP, more than double the U.S. ratio and considerably higher than even the famous bad example of Greece. The government has announced its intention to create inflation; it's goal is 2% per year, reversing the current deflation. To do that it is prepared to double the money supply.

If the deficit hawks know anything about how the world works, Japan should crash and burn. Conversely, if it doesn't, the Paul Ryans know nothing about how the world works.

Filibuster reform is being discussed again, as Harry Reid is admitting privately that he made a mistake in not pushing it harder at the beginning of this Congress.

It isn't just the unprecedented number of filibusters that is causing this, but the broader ambitions behind them. In the past, both parties have at times filibustered nominees that they had some personal objection to: the nominee was too extreme, too acerbic, or had some scandal in his or her past.

During the Obama years, though, Republicans have been using the filibuster as part of a global strategy to monkey-wrench parts of the government they don't like. No one has ever done that before.

For example, Republicans have blocked Richard Cordray's nomination as head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau -- not because they have uncovered something questionable about him, but because they don't think the CFPB should exist. As a post on Senator Shelby's web site put it in 2011: "44 Republican U.S. Senators today sent a letter to President Obama stating that they will not confirm any nominee, regardless of party affiliation, to be the Director of the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) absent structural changes". The stalemate has continued ever since.

Now the monkey-wrenching threatens to shut down the National Labor Relations Board. Legally, the NLRB can't function without a quorum, and unless some of Obama's nominees are confirmed it won't have one when the next member's term expires in August. So come August, it will be open season on workers' rights, because the federal government will be out of the picture. You don't have to change the law if you can shut down the enforcement agency.

Nurses explain the healthcare law in 90 seconds.

Four political scientists did an interesting study about the causes of political polarization. Their research survey describes the polarization process like this:

People are often unaware of their own ignorance (Kruger & Dunning, 1999), they seek out information that supports their current preferences (Nickerson, 1998), they process new information in biased ways that strengthen their current preferences (Lord, Ross & Lepper, 1979), they affiliate with other people having similar preferences (Lazarsfeld & Merton, 1954), and they assume that others’ views are as extreme as their own (Van Boven, Judd, & Sherman, 2012).

Then they did a series of experiments and found that people's certainty about policy proposals goes up after they're asked to give reasons why they hold their position, but goes down after they're asked to explain how the underlying proposals are supposed to work.

Across three studies we show that people have unjustified confidence in their mechanistic understanding of policies. Attempting to generate a mechanistic explanation undermines this illusion of understanding and leads to more moderate positions.

And they suggest:

that political debate might be more productive if partisans first engage in substantive and mechanistic discussion of policies before engaging in the more customary discussion of preferences and positions.

This matches my experience during 29 years of marriage: We're more likely to come to consensus on where to take a vacation if we first imagine what we would do in a variety of places, and only later express preferences.

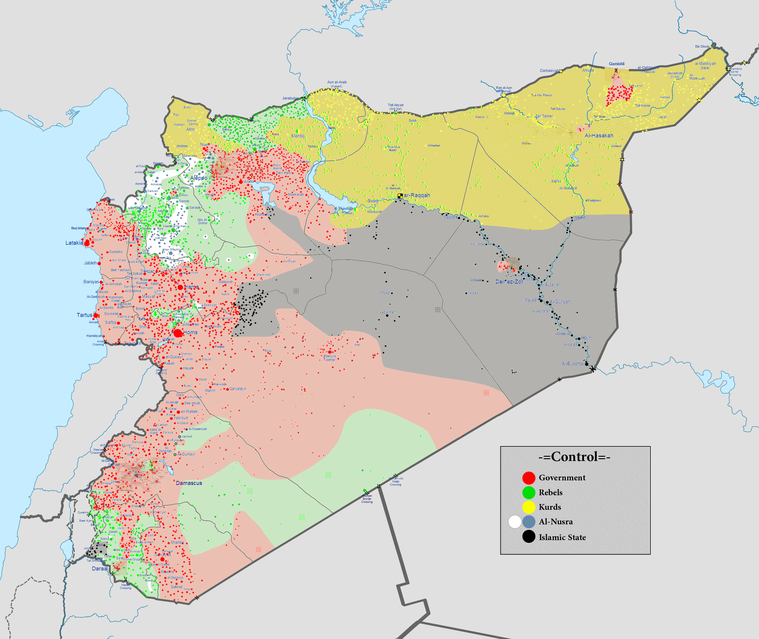

To follow up on last week's discussion of Syria, I found this map at Wikipedia. Red is Assad/Alawite/Shia controlled. Green is rebel/Sunni. Beige is Kurdish.

Since we're already talking Star Trek, here's a polarizing graphic:

No comments:

Post a Comment