Every report on [Trump's] 'flip-flopping' suffers by the implication that he had some sort of position in the first place. Nope. He said stuff.

This week's featured post is "Why cutting rich people's taxes doesn't create jobs".This week everybody was still talking about Trump's 100 Days

Matt Yglesias disputes the conventional wisdom that Trump's first hundred days have been a failure. It all depends on what you think he's trying to achieve. If he's trying to make a lot of money, he's doing very well.He goes on to outline the ways Trump is known to be profiting from his presidency, right down to the $35,000 the Secret Service has spent renting golf carts from Trump's Mar-a-Lago club so that they can follow him around the golf course.It's certainly true that Paul Ryan’s speakership of the House is failing, arguable that Mitch McConnell’s tenure as majority leader of the Senate is failing, and indisputably true that the Koch brothers’ drive to infuse hardcore libertarian ideological zeal into the GOP is failing.

But Trump isn’t failing. He and his family appear to be making money hand over fist. It's a spectacle the likes of which we've never seen in the United States, and while it may end in disaster for the Trumps someday, for now it shows no real sign of failure.

The Jay Rosen tweetstorm I pulled the opening quote from is a good summary of the problems the press has faced in these hundred days.

Forced to choose between inventing a language for a presidency without precedent and distorting the picture by relying on normal terms, newswriters have frequently chosen inaccuracy by means of a received language, even though they know there's nothing normal here.So they've referred to a one-page memo as a "tax plan" for lack of anything else to call it. And they speculate about the success or failure of Trump's "foreign policy" when it's not clear he has any policies. To say that he faces a "steep learning curve" assumes that he is learning, or even trying to learn.

The Guardian's Lawrence Douglas expresses my view on Trump's first hundred days: The institutions of American democracy held up under the initial assault. That doesn't mean the danger is over, but it is a good time to take note of

- our own accomplishments as protesters,

- the independence of our judges,

- the good work done by our embattled journalists,

- and the commitment of government employees to the missions of their organizations rather than the whims of a flighty new president.

In his sheer incompetence and inconstancy, Trump has emerged as our best bulwark against Trump. ... [His] very craving for adulation, the need to chalk up successes, the deep, even cynical, pragmatism also predicted that Trump would have no stomach for Bannon’s reign of terror. The banishing of Bannon from the innermost precincts of power can only be viewed as a good.

Along those same lines, I recently devoted a couple hours to watching Leni Riefenstahl's classic of Nazi propaganda, The Triumph of the Will, which was released in 1935, near the beginning of the Nazi regime. One of the things I learned is that Hitler was much better at this kind of thing than Trump has been. Hitler channeled the German people's pride, and reflected it back to them. In the scenes we see, he wastes no time telling Germans how great he is; other people do that. Hitler accepts the crowd's adulation and tells them how great Germany is, how great the German people are.

Trump's make-America-great-again campaign theme played to many of those same emotions. Like 1930s Germany (but to a lesser degree), a large chunk of the American public feels humiliated by the course of recent decades, and longs to feel national pride again. But Trump is too weak and too needy to get his ego out of the way and just make himself a mirror for the nation's self-admiration. Even when he's surrounded by adoring fans, he has to keep talking about himself and his own wonderfulness.

So Trump has character flaws that keep him from achieving the full authoritarian potential of the moment. Thank God for that.

Quantifying the unquantifiable: The WaPo fact-checkers have identified 488 false or misleading statements made by President Trump, or just under five per day.

the pace and volume of the president’s misstatements means that we cannot possibly keep up. The president’s speeches and interviews are so chock full of false and misleading claims that The Fact Checker often must resort to roundups that offer a brief summary of the facts that the president has gotten wrong.

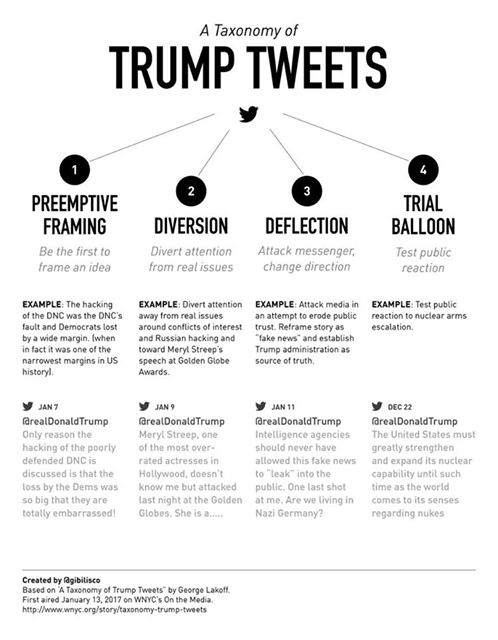

I've long been a fan of cognitive scientist George Lakoff. Here's an instructive graphic from him.

and his self-serving one-page tax "plan"

Remember back when that black guy was president and the size of the federal debt was an existential threat to the country? Deficits were going to turn us into Greece or something?Oh, never mind. Let's cut taxes.

Describing a single-page memo as a "tax plan" is a bit of a stretch, but the administration wanted to get a proposal in under the 100-day window, and this was the best it could do. For example, it suggests lowering the number of tax brackets from seven to three (10%, 25%, and 35%), but doesn't specify the income ranges those brackets apply to. So there's no way to know exactly what the effect will be on any particular person's taxes, like yours.

One person who clearly will pay less tax, though, is Donald Trump. He claims the opposite, because of course he would claim that. (I no longer think of Trump's falsehoods as lies. I think he simply says whatever sounds good, and any positive or negative correlation with reality is purely incidental.) And no one can conclusively prove otherwise, because he won't release his tax returns. But everything we know about the Trump Organization matches up well with the cuts he's proposing on things like pass-through corporations.

He proposes eliminating most tax deductions, but keeping the deduction on mortgage interest. This also has self-serving benefits: Without that deduction, the price the Trump Organization could charge for the condos it has for sale would drop considerably.

Plus, we have two pages of Trump taxes from 2005.

That return also implied that without the alternative minimum tax, which Trump wants to repeal, he would have paid less than 3.5 percent of his income in federal income taxes. Cutting the pass-through rate while repealing the AMT would probably reduce his tax burden to roughly half that level. Instead of paying $38 million, he could've paid less than $3 million.So if we apply his proposal retroactively to his 2005 taxes, Trump would pay less than a tenth of what he paid before, and save himself $35 million.

Has any previous president ever proposed legislation that would make himself richer at the rate of $35 million a year? I doubt it.

One reason we're talking about a one-page memo rather than an actual piece of legislation Congress might vote on is that Trump has yet to appoint the person responsible for writing that bill.

For 470 of 556 key positions that require Senate confirmation, Trump has yet to announce a nominee at all, according to a tracker maintained by the Partnership for Public Service and Washington Post. In nearly half the cases where he has announced a nominee, the White House hasn't formally sent the nominations to the Senate, awaiting clearance from the Office of Government Ethics and an FBI background check.One of those 470 empty slots is the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Tax Policy.

I may argue with his arithmetic, but I'll give CNBC's Jake Novak credit for saying openly what other conservatives believe silently:

Unless Social Security, Medicare, and defense are significantly reformed and cut, not even a 100-percent tax increase will get us out of debt. And the myth that the public will not tolerate changes and cuts to those programs at all is just that -- a myth.So our budget problem, according to Novak, isn't that so many billionaires and giant corporations pay zero tax; or that the ones that do often pay a lower rate than secretaries; our problem is that not enough old people are eating cat food or dying in the street.

And for the sake of argument, let's say he's right: Suppose that in the long run we really do have to cut entitlement programs. That's no excuse for ignoring the revenue side of the equation: We'd have to cut entitlements less if the rich were paying more tax.

and Obama getting paid to speak

In September, Barack Obama is scheduled to speak at a conference on health care sponsored by Wall Street firm Cantor Fitzgerald. He'll receive a $400,000 speaking fee.I'm of two minds about this. On the one hand, liberals could really use a saint about now, and Obama would make a good one. I would love it if he spent the rest of his life living humbly, saying wise things, and inspiring a new generation of social justice warriors.

On the other hand, I'm always skeptical when we raise standards just in time for them to apply to the black guy. Ex-presidents command large fees on the speaking circuit, and have done so at least since Ronald Reagan's $2 million tour of Japan. They also sell a lot of books (that goes back to Ulysses S. Grant) and make big bucks that way. Most of them haven't really needed the money (Grant did), so foregoing these big paydays doesn't seem like that much to ask. But why start with Obama?

Any big cash conduit could be used for bribery, so we ought to stay alert for that. But while $400K would be a huge amount of money to all but the richest Americans, it seems to be the going rate for the small number of speakers who have Obama's level of star power. (BTW: This was also my opinion of Hillary Clinton's speeches. Getting her on your speaking list put your conference or lecture series on the map. That was worth the price to a lot of organizations, without any assumption that they'd get favorable treatment in some future administration.)

One way conservatives like to tie liberals in knots is by building purity traps. Isn't it hypocritical that Al Gore has a big home that uses a lot of electricity, or that Bill McKibben flies, or that Warren Buffett tries to minimize his company's tax bill, or that all of us who claim to care about the homeless aren't living in cardboard boxes ourselves?

We need to stop cooperating with this kind of stuff. There is no limit to how pure you could possibly be, and no one who lives inside an unjust system can be entirely untainted by that injustice. If Obama decides to go for sainthood, I'll cheer him on. But I think that should be his decision.

but I wish I understood the infighting among Democrats and other liberals

The most important issue I haven't been writing about is the continuing struggle between so-called "establishment" Democrats (who mostly supported Hillary in the primaries) and so-called "progressives" (who mostly supported Bernie). I haven't written about it for a very specific reason: I don't understand it, and I don't want to compound the ambient cluelessness by adding my voice to it.At a point in our political history where anyone to the left of John Kasich ought to be uniting to protect American democratic traditions against Trump, an incredible amount of vitriol is going back and forth between people who are all some distance from that line.

From the Left, Cornell West is writing:

Even as we forge a united front against Trump’s neofascist efforts, we must admit the Democratic party has failed us and we have to move on. Where? To what? When brother Nick Brana, a former Bernie campaign staffer, told me about the emerging progressive populist or social democratic party – the People’s party – that builds on the ruins of a dying Democratic party and creates new constituencies in this moment of transition and liquidation, I said count me in.Bernie himself is on a muddled "unity tour" with newly elected DNC chair Tom Perez, in which he denies being a Democrat.

Meanwhile, Bernie is facing criticism for supporting a candidate who's squishy on abortion rights, and for not bridging the gap that kept blacks and Hispanics from supporting him in 2016.

With the diverse Democratic base in the southern states being a major reason why Sanders lost, you’d think that his movement would make a major effort to reach out to Black voters and find a way to meet them on the issues that they care about.

Nope. Instead, we are seeing a doubling down on a focus of the white working class and hostility to identity politics.

I'm hoping to understand all this better and write something useful about it before long. But here's where I'm starting: Everybody is talking about "the Democratic Party" is if it were a much more solid entity than it really is. The Democratic Party is nothing more or less than the sum total of the people who vote in Democratic primaries. If a unified movement of people -- whether from the left or the center (or even from the far right, if they could somehow manage it) -- can win those primaries, then the party is theirs.

That's the test: Run candidates. Turn people out to vote for them. And if you lose, don't blame other factions for running their own candidates and turning out people to vote for them. That's just how democracy works.

and you might also be interested in

Congress has a deal to keep the government open for the rest of the fiscal year, which ends September 30. It will be voted on this week.If you've read any John le Carré Cold War spy novels, you're familiar with the subtle ways intelligence agencies set each other up: Leak this document, let that defector escape to tell some particular story, arrest somebody who otherwise would be in a position to debunk that story, and so on. One side leaves a trail of bread crumbs that they know someone on the other side will follow to a predictable result, which he will then believe because of the effort he had to invest to put all the pieces together.

In "Pathology of a Fake News Story", Leon Derczynski claims those tactics are now being used on journalists and even on ordinary people who try to get to the bottom of things.

Imagine this. You’re an educated person with a bit of time, and you visit the doctor with a long-standing non-threatening complaint. They suggest a medicine you’ve tried before, or perhaps you’d like to try a new one. Prudently, you check out the suggested drug. You read a few articles about it, but they look like the typical marketing literature. You find four or five academic papers on the drug; most of the trials look good, with a benefit in the majority of cases. There’s one that’s inconclusive, but it’s in a less major journal, with a small sample size. You then go and check out a few review sites; most of the reviews are positive — the drug’s no panacea, but it’s better. A few of the reviews are very negative, but seem to be from people who are a little bit crazy, not using the drug right, have many other conditions, and so on. So you conclude, it looks legitimate; none of the stories look controlled, and everywhere you look, you see what you’d expect to see from a decent drug. Except it’s not. Everything you’ve read — all the end-user comments, all the peer-reviewed articles, are shills, put there by the pharma corporation to make their drug look good, and make it look good in a way that “smells” legitimate.The implications of this seem terribly nihilistic to me. The future looks like a place where, no matter how careful you are, you can't believe anything about anything, because a disinformation AI might always be one step ahead of you. How can I be sure that Leon Derczynski even exists? How can you be sure that I do?This astroturfing practice is well-studied; Sharyl Attkisson has a talk on it that’s worth checking out. The central idea is to place stories, evidence and so on in the locations that a knowledgeable, [skeptical] person would search, and give them the imperfections and angle that we all expect to see in genuine evidence.

The next step seems kind of clear: if you want to control the media, you can do so by astroturfing for journalists. Where will they look? What does good, genuine evidence look like for them?

To no one's great surprise, there still is no ObamaCare repeal coming out of the House.

The New York Times needs to accept that there's no way to include a far-right columnist in its stable without becoming a conduit for disinformation. That was the lesson from Bret Stephens first NYT column "Climate of Complete Certainty", which fits nicely into the fossil-fuel industry's doubt-raising agenda on climate change: Don't just sponsor outright denial, also put reasonable-sounding people out there to raise enough doubt to prevent action.

The column is full of strawman arguments against radical environmentalists who are pushing scare scenarios beyond the scientific evidence. But strangely, Stephens offers no specific examples. He raises the stereotype; that's enough.

For a more detailed response, see Brian Kahn.

and let's close with some cartoons

Polish cartoonist Paweł Kuczyński creates many striking images, like this one:

No comments:

Post a Comment