The world has never had a good definition of the word liberty, and the American people, just now, are much in want of one. We all declare for liberty; but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing. With some the word liberty may mean for each man to do as he pleases with himself, and the product of his labor; while with others the same word may mean for some men to do as they please with other men, and the product of other men's labor. ... The shepherd drives the wolf from the sheep’s throat, for which the sheep thanks the shepherd as a liberator, while the wolf denounces him for the same act as the destroyer of liberty.

- President Abraham Lincoln (April 18, 1864)

This week's featured post is "The Emotional Roots of Political Polarization".

This week everybody was talking about Build Back Better

Joe Manchin announced on Fox News Sunday that he could not vote for President Biden's Build Back Better bill, effectively dooming it. The White House released an angry statement in response, ratifying the breakdown in the Biden/Manchin relationship.

For half a year, Manchin has delayed progress on the bill, raising the question of whether he would eventually come through after he had whittled the proposal down to his liking, or if he was simply stringing Biden along. Now it looks like the latter.

Manchin's decision sinks a number of popular proposals, including lowering prescription drug prices, continuing the child tax credit, and mitigating climate change.

and January 6

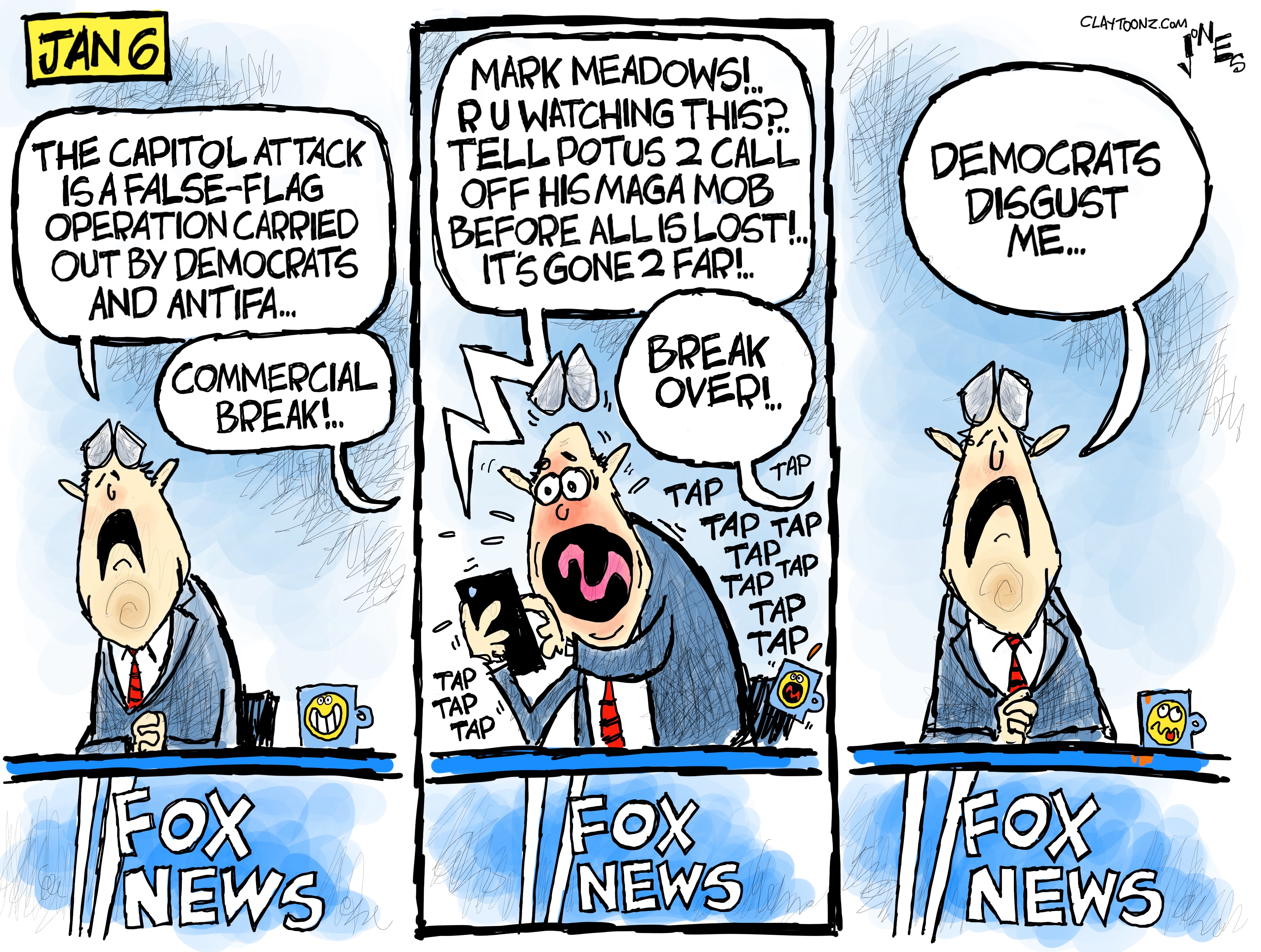

During the House debate on whether to find Trump Chief of Staff Mark Meadows in contempt of Congress for his defiance of a subpoena, (the contempt resolution passed) members of the January 6 Committee revealed a number of text messages Meadows had received on January 6 from various conservative luminaries, including Fox News hosts, at least one member of Congress, and Donald Trump Jr.

The point of publicizing these texts was that they emphasize the need for Meadows' testimony. But they make another important point about the subsequent cover-up of January 6: As much as Trump propagandists try to claim that (1) the Capitol insurrection wasn't a big deal, and/or that (2) Trump bore no responsibility for it, they knew at the time that those things weren't true.

The texts plead with Meadows to get Trump to stop the violence, which demonstrate their authors' belief at the time that Trump was controlling the violence. The texts would make no sense if the demonstrators were basically peaceful, or if the violence were a false-flag operation sparked by antifa, as Trumpists like to claim.

As Trump's attempt to block the January 6 Committee's access to documents from his administration goes to the Supreme Court, Vox points out what a flimsy claim he has under existing precedents. If the Court's partisan majority wants to protect him, they'll have to invent new law.

They might, but I'll bet not. Roberts won't go for it, and he only needs to convince one more conservative. Either Gorsuch or Kavanaugh might be that deciding vote. If the Court doesn't find against Trump, they'll manufacture an excuse to keep the legal wrangling going in hopes that a new Republican House majority will make the case moot by sacking the whole committee in 2023.

The Atlantic follows freshman Republican Rep. Peter Meijer through the events of January 6.

On the House floor, moments before the vote, Meijer approached a member who appeared on the verge of a breakdown. He asked his new colleague if he was okay. The member responded that he was not; that no matter his belief in the legitimacy of the election, he could no longer vote to certify the results, because he feared for his family’s safety. “Remember, this wasn’t a hypothetical. You were casting that vote after seeing with your own two eyes what some of these people are capable of,” Meijer says. “If they’re willing to come after you inside the U.S. Capitol, what will they do when you’re at home with your kids?”

That account led WaPo's Aaron Blake to write "The role of violent threats in Trump's GOP reign".

This is one panel of a Tom Tomorrow comic in which the news anchors outline the run of recent bad news.

AP reviewed "every potential case of voter fraud in the six battleground states disputed by former President Donald Trump" -- all 475 of them.

The cases could not throw the outcome into question even if all the potentially fraudulent votes were for Biden, which they were not, and even if those ballots were actually counted, which in most cases they were not.

The review also showed no collusion intended to rig the voting. Virtually every case was based on an individual acting alone to cast additional ballots.

Not all Republicans are comfortable centering their Party on a lie that undermines democracy. Wisconsin State Senator Kathy Bernier called out her fellow Republicans.

A Delaware judge has ruled that Dominion Voting System's lawsuit against Fox News can go forward. At issue is whether Fox knew at the time that the election-fraud claims it was making against Dominion were baseless.

and Omicron

The pandemic numbers continue to increase: New cases per day in the US are up to 133K, a 21% rise over two weeks. Deaths are inching up: 1296 per day (7-day average), up 9%. Hospitalizations are at 69K, up 16%.

The records were set last January: 248K cases per day on January 11, deaths at 3336 per day on January 15, 140K hospitalized on January 5.

Omicron spread in the United Kingdom is running ahead of the US, so it may provide a glimpse of our future. The UK has been setting new-case records, and London bars and restaurants have begun shutting down on their own, creating a "lockdown by stealth".

The economic consequences could be more dire this time around, because the government isn't providing support to businesses that close temporarily. That could happen here too.

There’s no federal money left to keep restaurants open. The aid for concert halls and other customer-starved performance spaces has nearly gone dry. Federal officials ended their primary effort that pumped money into small businesses with sagging balance sheets, and they stopped paying out extra sums to workers who are out of a job.

Like the original strain of Covid-19, Omicron is hitting the US first in New York City. I'm writing these words in Florida, which has become a low-Covid oasis since the summer surge passed. But a new outbreak seems to be starting in Miami.

Ed Yong's article in The Atlantic does a great job of explaining the biology of Omicron in terms ordinary people can understand.

The coronavirus is a microscopic ball studded with specially shaped spikes that it uses to recognize and infect our cells. Antibodies can thwart such infections by glomming onto the spikes, like gum messing up a key. But Omicron has a crucial advantage: 30-plus mutations that change the shape of its spike and disable many antibodies that would have stuck to other variants.

... In terms of catching the virus, everyone should assume that they are less protected than they were two months ago. As a crude shorthand, assume that Omicron negates one previous immunizing event—either an infection or a vaccine dose. Someone who considered themselves fully vaccinated in September would be just partially vaccinated now (and the official definition may change imminently). But someone who’s been boosted has the same ballpark level of protection against Omicron infection as a vaccinated-but-unboosted person did against Delta.

... Even if Omicron has an easier time infecting vaccinated individuals, it should still have more trouble causing severe disease. The vaccines were always intended to disconnect infection from dangerous illness, turning a life-threatening event into something closer to a cold. Whether they’ll fulfill that promise for Omicron is a major uncertainty, but we can reasonably expect that they will. The variant might sneak past the initial antibody blockade, but slower-acting branches of the immune system (such as T cells) should eventually mobilize to clear it before it wreaks too much havoc.

Data continues to come in.

Moderna’s results show that the currently authorized booster dose of 50 micrograms — half the dose given for primary immunization — increased the level of antibodies by roughly 37-fold, the company said. A full dose of 100 micrograms was even more powerful, raising antibody levels about 83-fold compared with pre-boost levels, Moderna said.

But not all the results are encouraging:

All vaccines approved in the United States and European Union still seem to provide a significant degree of protection against serious illness from Omicron, which is the most crucial goal. But only the Pfizer and Moderna shots, when reinforced by a booster, appear to have success at stopping infections, and these vaccines are unavailable in most of the world.

The other shots — including those from AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson and vaccines manufactured in China and Russia — do little to nothing to stop the spread of Omicron, early research shows.

Six anti-vax protesters were arrested for a sit-in at the Cheesecake Factory in New York City. They barged in after refusing to show their vaccine cards, as the city requires.

The protesters compared the employees who refused to serve them to Nazis, and claimed a constitutional right not to reveal their private medical information. (And that is true, of course. But there is no constitutional right to eat at Cheesecake Factory.)

Because the sports leagues do such regular testing, they are spotting mild and asymptomatic Covid cases that the larger society misses. In the last two weeks, Covid's effect on games has greatly increased. We're starting to hear calls for the leagues to shut down again.

Fox News has been actively denying the well-established link between vaccine status and hospitalization for Covid.

When it comes to pronunciation, I am on Team OH-micron rather than Team AH-micron. To me, it's obvious: omicron is a companion to omega (little-o/big-o) and nobody says AH-mega.

and inflation

The Bank of England became the first central bank to start raising interest rates in response to rising inflation.

The Federal Reserve is also responding, but more slowly. The Fed controls short-term interest rates on dollar deposits more-or-less directly, through the rates that it charges to banks; it affects long-term rates indirectly, by purchasing bonds in the market.

The Federal Reserve said on Wednesday it would end its pandemic-era bond purchases in March and pave the way for three quarter-percentage-point interest rate hikes by the end of 2022 as the economy nears full employment and the U.S. central bank copes with a surge of inflation.

Paul Krugman writes a readable account of the history and causes of inflation, and summarizes the debate between economists who think the current inflation is transitory and those who expect it to persist. Krugman himself is on Team Transitory, but he acknowledges that the current bout has already gone further than he expected, and I think he presents the debate fairly.

The problem, as Krugman presents it, isn't so much that demand has soared as that during the pandemic it shifted from services into goods.

The caricature version is that people unable or unwilling to go to the gym bought Pelotons instead, and something like that has in fact happened across the board.

Services tend to be local, but goods depend on a global supply chain, which hasn't broken, but hasn't responded flexibly enough to accommodate increased demand. This, Krugman believes, will work itself out: As the pandemic recedes, service consumption will go back up, and supply-chain adjustments are already being made.

A second factor has been workers' reluctance to return to the labor market, the so-called Great Resignation, which is forcing wages up. Krugman confesses he doesn't understand exactly what is causing this or how quickly workers will come back.

A third factor in inflationary periods of the past has been psychological: Businesses raise prices and workers demand higher wages because they're convinced that other prices will go up. In other words, inflation becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. He doesn't see evidence of this happening yet, but acknowledges that it could.

but you might want to think about this

Take a look at James Muldoon's article "Regulating Big Tech is not enough. We need platform socialism." I'm not sure how these specific ideas would work in practice, but I think we need to expand the universe of possible solutions to our social-media problem.

In practice, all participatory democracy processes -- the daily hours-long open meetings of the Occupy movement being a prime example -- run into the widespread desire for what I like to call Disneyland authoritarianism: Somebody should set things up so that I don't have to worry about how anything works, and I don't care if they exploit me a little as long as they also provide an enjoyable experience.

Disneyland authoritarianism works fine in a place like Disneyland, where management knows that you can easily walk out and never come back if you don't like how you're treated.

A lot of democratic-on-paper organizations end up running in a Disneyland authoritarian manner, because only a small group of people can be bothered to show up to decision-making meetings and man the bureaucracy. As long as the insider cabal keeps providing the services that the larger community expects and maintaining an acceptable level of quality, most people are content to fall into the role of customers rather than citizens. And that can be OK, as long as the processes are transparent and the cabal's boundaries are permeable.

Small-town school boards are a good example. As long as local schools function at an acceptable level, most people can't be bothered to participate, or even to vote in school-board elections. Democratic control exists mainly as a fail-safe, but that's enough to keep authoritarian abuses at bay.

Disneyland authoritarianism becomes problematic when essential systems of everyday life depend on decisions made inside a Disneyland by a cabal that isn't transparent or permeable. That's the problem with social-media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

In the beginning, free privately owned social media apps seemed like a good deal. We got to stay in touch with our friends, participate in communities of interest, and so on. Sure, they harvested our data and used it to target ads at us, but that seemed like a small price. If we didn't like their online Disneylands, we could leave them and never come back.

But now we've gotten into a situation where democracy itself is strongly influenced by what happens inside social media platforms that are organized to maximize their owners' profit. Disinformation and polarization are good for profits, but not for us as individuals, and not for our country or the world. But we can't join the decision-making group, or even find out what they're doing. And while we can walk away from the platforms themselves (at some cost to our ability to fully participate in society), we can't isolate ourselves from their effect on our democratic systems.

and you also might be interested in ...

A heart-breaking article about how conspiracy theorists hurt the very people they claim to help, like the children they are misguidedly trying to save from sex trafficking, as well as the actual sex-trafficking investigations they monkey-wrench.

For years we've been hearing about American airstrikes that go wrong and kill innocent people. This week the NYT published a series based on internal Pentagon assessments, claiming that

the American air war has been plagued by deeply flawed intelligence, rushed and imprecise targeting and the deaths of thousands of civilians, many of them children.

... Taken together, the 5,400 pages of records point to an institutional acceptance of civilian casualties. In the logic of the military, a strike was justifiable as long as the expected risk to civilians had been properly weighed against the military gain, and it had been approved up the chain of command.

The Pentagon records point to an official count of about 1,600 civilian deaths from airstrikes in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan since the official American ground war ended in Iraq in 2014. The Times' estimate is much higher.

Christine Emba brings some common sense to the critical race theory disinformation campaign. Is math racist? Of course not. But the subject can be taught and its classes organized in racially biased ways.

Now we know what Putin's sabre-rattling in Ukraine is about: He wants NATO to renounce expansion or other interference in what he imagines to be the Russian sphere of influence.

Bruce Springsteen's half-billion-dollar deal with Sony induced the NYT to explain the new economics of the music business.

The intrepid war correspondents of Fox News are on the front lines as the War on Christmas enters its 17th year. CNN's John Avalon looks back at the origins of this annual conflict. He interviews Alisyn Camerota, who is now with CNN, but was at Fox back in those early days of the War, when "marching orders" to give national 24/7 coverage to any local nativity-scene controversy "so that you begin to think it's a national crisis" came down from Fox president Roger Ailes.

The turning of something that unifying, something that really should transcend partisan politics in every way, into something divisive that people can fixate on and feel fear about -- that's a real trick. And it's also a sign of sickness, a sign of partisanship seeping into every element of our lives at the hands of people who are trying to gin up this anxiety.

The Sackler family had negotiated a sweet deal for itself: The family's company, Purdue Pharma, would take full responsibility for its role in creating the opioid crisis, and then declare bankruptcy. That plan would generate $4 billion to pay out to victims, but shield the family from any further lawsuits, letting them walk away with their own billions intact.

But a federal judge threw that agreement out Thursday, saying that the New York bankruptcy court didn't have the authority to offer the family that protection.

The Sackler family is the subject of the best-selling book Empire of Pain, and the HBO documentary The Crime of the Century.

and let's close with something seasonal

Trust Stephen Colbert to remind us of what the Christmas season is really about: blockbuster movies. This year in particular marks the 20th anniversary of The Fellowship of the Ring, the first film in Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings trilogy. Colbert commemorates this milestone as they undoubtedly would in Rivendell, with rap.

No comments:

Post a Comment