When people are moving heaven and earth to block an investigation, you've got to ask: What is it they're afraid will be revealed?

- Senator Angus King (I-Maine)

This week's featured post is "The Bipartisanship Charade is Almost Over".

This week everybody was talking about the Trump grand jury

Tuesday, The Washington Post reported that Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus R. Vance Jr. had "convened the grand jury that is expected to decide whether to indict former president Donald Trump, other executives at his company or the business itself".

Vance has had Trump's tax returns for about three months, after fighting a years-long legal battle to obtain them. In March, The New Yorker had a long article on Vance and the Trump investigation, which it described as

a broad examination of the possibility that Trump and his company engaged in tax, banking, and insurance fraud. Investigators are questioning whether Trump profited illegally by deliberately misleading authorities about the value of his real-estate assets. [Former Trump lawyer Michael] Cohen has alleged that Trump inflated property valuations in order to get favorable bank loans and insurance policies, while simultaneously lowballing the value of the same assets in order to reduce his tax burden.

The New York Times also claimed in September to have seen Trump's tax returns, and a more recent article summarizes his questionable tax avoidance strategies.

The vision of Trump in an orange jumpsuit is so compelling that Democrats are easily tempted to waste time speculating about how or when it might happen. But we just don't know. When Republicans investigate Democrats -- like the Starr investigation of Bill Clinton or the FBI probe into Hillary's emails -- those investigations leak, because politics was the point from the beginning; the investigation was never about finding a serious crime and taking it to court. But from Mueller and Comey through to Vance, the various investigations into Trump have not leaked.

So despite the many hours of coverage this topic has attracted this week, the legitimate tea-leaf reading can be summed up fairly quickly: Vance must believe he can prove that somebody committed a crime. Maybe it's Trump. Or maybe it's somebody Vance hopes to flip against Trump, like Trump Organization CFO Allen Weisselberg or one of Trump's children.

But financial charges against rich men are hard to make stick, both because plutocrats hire good lawyers, and because they can always hide behind underlings. ("I just the sign the documents my staff tells me to sign. I couldn't possibly read them all.") Convicting Trump will require getting some of those underlings to flip. Somebody needs to tell a jury, "I explained this to him and he told me to break the law."

One thing I can predict: If Trump faces charges, he will instantly transform from a brilliant businessman to Sergeant I-Know-Nothing Schultz. Something similar happened when he answered questions (in writing) for Bob Mueller. After years of telling us how smart he is -- "I have a very good brain" -- Trump suddenly sounded like an escapee from the dementia ward. No matter what Mueller asked, Trump's answer was some form of "I don't remember."

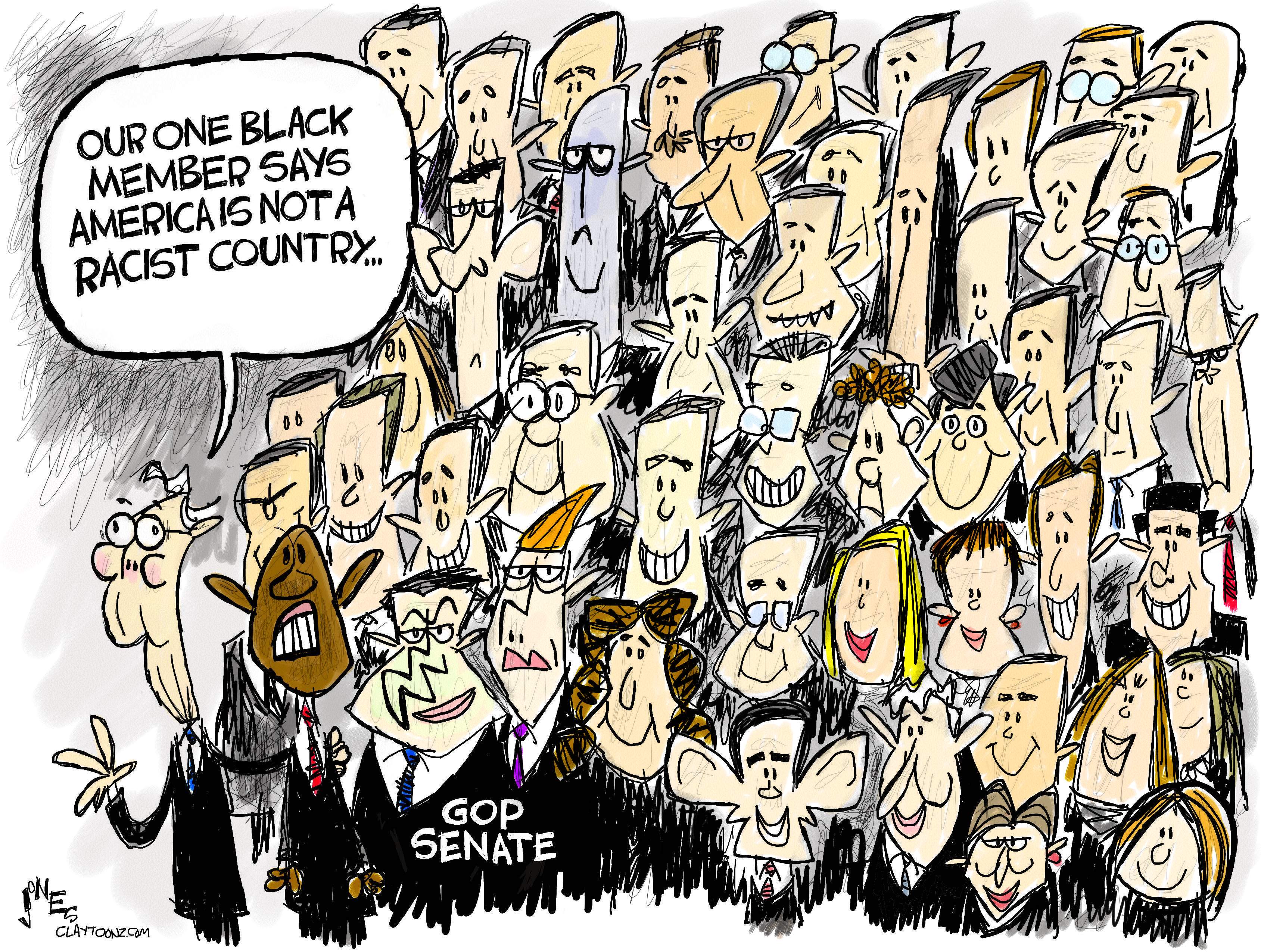

and anniversaries of racist violence

Tuesday marked one year since George Floyd's murder. Tomorrow is the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Massacre.

With regard to George Floyd, the big question raised by the one-year mark is: How much has changed? And the answer is: some things, but not nearly enough.

The biggest change, in my opinion, is the precedent set by the Chauvin trial itself: George Floyd's killer was convicted of murder, and other Minneapolis police officers testified against him. It's still possible to argue that Chauvin should have been convicted of first-degree murder rather than second, but "Police always get away with it" isn't true any more.

Laws have also changed, at least somewhat. Numerous cities and states have passed some kind of police reform, and some version of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act may get through Congress this summer. Mostly the reforms center around when and how police are allowed to use force.

Colorado now bans the use of deadly force to apprehend or arrest a person suspected only of minor or nonviolent offenses. Also, though many states permit the use of deadly force to prevent “escape,” five states enacted restrictions or prohibitions on shooting at fleeing vehicles or suspects, a policy aimed at preventing deaths like that of Adam Toledo, a 13-year old shot by Chicago police during a foot chase. Additionally, 9 states and DC enacted complete bans on chokeholds and other neck restraints while 8 states enacted legislation restricting their use to instances in which officers are legally justified to use deadly force.

But the national shock of the Floyd murder, the millions of Americans who demonstrated against it, and the many white people who finally seemed to recognize the problem, appeared (just for a moment) to promise much more. Perhaps the nation would fundamentally rethink public safety and the role of police. "Defund the Police" may have inspired more backlash than reform, but nonetheless the idea was getting out there: Not every kind of disorder is best handled by people with guns. Maybe some of the money that now passes through police departments should instead go to unarmed first responders trained in mental health or social work. Maybe traffic tickets could be written by civil servants who can't shoot people.

Despite a few tentative steps, that promise has gone unfulfilled. The symbol here is the Minneapolis City Council's pledge to "end policing as we know it", which came to nothing.

Finally, the bottom line has not budged: The unjustified killing of Americans by police continues, and the victims continue to be disproportionately non-white. We know this both anecdotally -- Rayshard Brooks, Daunte Wright, Ma’Khia Bryant, Adam Toledo -- and statistically.

Any individual killing has details that can be debated, but the larger picture is undeniable: No comparable country has this problem to any similar degree.

If we were rational about this problem, US police departments would be flying folks in from Norway or England to explain how they police modern cities without killing people. But instead, American cops have been paying "experts" like Dave Grossman of the Killology Research Group to tell them how to be better "warriors" on the "battleground" of American cities.

The 100-year anniversary of Tulsa raises a different set of issues: how we teach and commemorate US history. When I was growing up in the 1960s, "race riot" meant outbreaks of violence in Black sections of Los Angeles or Detroit. Race riots were yet another reason for Whites to fear Blacks, and to vote for "law and order" candidates like Richard Nixon or George Wallace.

Only decades later did I discover that often Whites have been the rioters. I'm not sure when exactly I first learned about the destruction of the prosperous Greenwood district in Tulsa, but it has definitely been in the last ten years.

When it was over on June 1, 1921, 35 square blocks of what was nicknamed Black Wall Street lay in smoldering ruins. There were reports that bodies were thrown into the Arkansas River or buried in mass graves. Hundreds of survivors were rounded up at gunpoint and held for weeks at camps.

No one was ever held accountable for the lives lost or the property destroyed. Insurance claims filed by homeowners and business owners were rejected

I didn't learn about that in school. In 2014, I described my high school education in Black history like this:

Except for Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver, [the Black people Lincoln emancipated] vanished like the Lost Tribes of Israel. They wouldn’t re-enter history until the 1950s, when for some reason they still weren’t free.

So: Black people in Tulsa in 1921? What Black people?

Fortunately, ignorance about the Tulsa riot is declining. Recently, Tulsa has become a touchstone in popular culture's re-examination of America's racial history. It plays a key role, for example, in both the Watchmen and Lovecraft Country series on HBO.

Similarly, I first heard of Ida B. Wells and her anti-lynching campaign when I went to the National Museum of African American History in 2018. Ditto for the Harlem Renaissance. I mean, are you sure Black culture bloomed in the 1920s? Did we even have Black people then?

So as Republican legislatures ban "critical race theory" from schools and protect Confederate statues against liberals who want to "erase history", it's worth remembering Tulsa. The history of white supremacy in America, and the racist violence that has maintained it, was erased from public consciousness long ago. We need efforts like the 1619 Project to recover the national memories that white racist propaganda has made us forget.

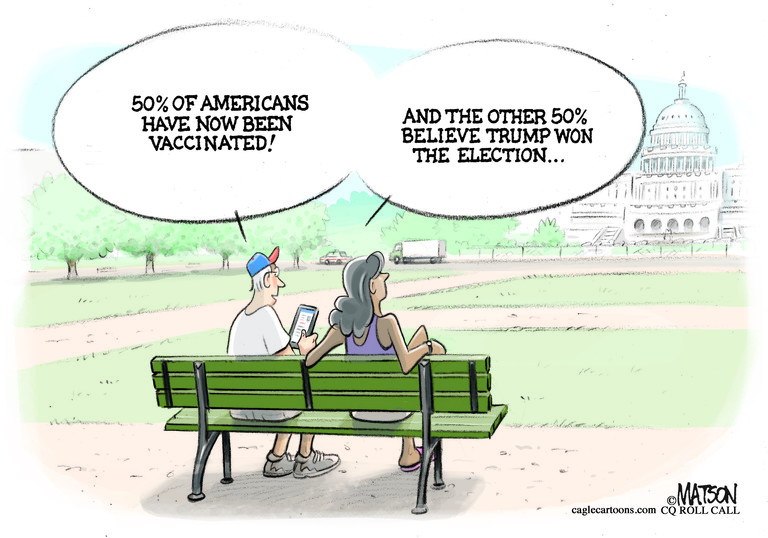

and the pandemic

Recent trends continue: Vaccinations continue to rise while new cases and deaths fall. The 7-day average for daily new cases is down to 21K, after peaking over 250K in mid-January. The number of people with at least one dose of the vaccine has crossed 50%.

A new poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation suggests that we might get to the 70% vaccinated level that some experts say would give American society herd immunity. In particular, some holdout groups are starting to come around, particularly Latinos and people without college degrees.

Sometimes trends advance because nobody wants to be on the fringe. As long as some friend you think of as more sensible is holding out, joining the trend doesn't seem urgent. But at some point, it's just you and people you think of as wackos.

I kinda-sorta get how a person might mistrust the government and the medical establishment so much that they avoid vaccination. Last summer, when it looked like Trump might push the FDA to approve a vaccine prematurely so that he could tout it as a campaign issue, I was skeptical myself. But that didn't happen, millions of people have been vaccinated with few side-effects, and the case-counts and deaths have been dropping. So I got vaccinated.

But even in the Trump-corrupts-the-FDA scenario, it never occurred to me that I might protest against other people taking the vaccine, just like it never occurs to me to hassle people who wear masks in situations where I don't think they're necessary. (If you want to wear a mask when you're alone in your own home, go for it. Why should I care?) After all, the point of not taking the vaccine would have been to make my own risk assessment, which I should be free to do in all but the most dire circumstances. But using my judgment to overrule other people's risk assessments is something else entirely.

Well, I'm clearly not thinking like a true right-wing loony. In fact, people are protesting against the vaccine, including a Tennessee woman -- what got into Tennessee this week? -- who shouted "No vaccine!" as she drove her SUV through a vaccination tent "at a high rate of speed", threatening both the medical staff and ordinary people who came to be vaccinated. She's been arrested and charged with seven counts of reckless endangerment.

Apparently, this is a thing. The Washington Post reports:

Demonstrations have popped up in vaccination sites such as high schools and racing tracks in recent months, and anti-vaccine protesters temporarily shut down Dodger Stadium after maskless people blocked the entrance to one of the country’s largest sites.

I also can't explain why hitting people with a car has become such a popular tactic on the right, to the point that Republican legislatures are starting to write it into law.

you also might be interested in ...

A lady just came up to me and said “Speak English, we are in San Diego.” So I politely responded by asking her “how do I say ‘San Diego’ in English?” The look of bewilderment on her face made it feel like a Friday.

Apparently by coincidence, two once-crazy ideas are now being treated more respectfully: the lab-leak theory of Covid, and the existence of UFOs.

I'm not really in a position to say anything definitive on either theory, but I do think it's important not to jump too far: Even if Covid leaked out of a Chinese lab, that doesn't mean it was engineered by humans or released as a bioweapon attack. More likely, the lab collected a bunch of viruses to study, and one got loose.

Wired's Adam Rogers does a good job of separating ordinary scientific uncertainty from what he calls "weaponized uncertainty".

When scientists say “We’re not totally sure,” they mean their analysis of some event or outcome includes a statistical possibility that they’re wrong. They never go 100 percent. Sometimes they think they might possibly be wronger than others. This is the world of confidence intervals, of mathematical models and curves, of uncertainty principles. But non-scientists hear “We’re not totally sure” as “So you mean there’s a chance?” It’s the mad interstitial space between scientific—let’s say, statistical—uncertainty and the meaning of normal human uncertainty. This is where “just asking questions [wink]” lives.

It’s a subtle difference. When Tony Fauci says he’d like to get more certainty, for example, he most likely means that, yeah, all things being equal, it’s better to know than not know—especially if that’s the way the political winds are blowing.

But when political actors like senators and right-wing TV commentators talk about this uncertainty, this doubt, they’re trying to jam a crowbar into this gap in understanding and lever it open. They’re still hinting that the Chinese government is doing something sneaky here, something warlike—and that even the scientists think it’s possible. Because if they can seem to have the backing of science, they can use that power elsewhere. They can bang shoes on tables about Biden administration inaction and Chinese skullduggery to distract from their lies about the election, about attempts to curtail voting rights, about the January 6 insurrection, about efforts to get the world vaccinated against the disease they claim to want to understand better.

FWIW, I live next door to a biologist, who tells me that Mother Nature is still much better at constructing nasty viruses than we are. Apparently, engineering the Andromeda Strain is more difficult than the movies would have you believe.

Same point about UFOs: Pentagon videos of literal "unidentified flying objects" do not prove that aliens walk among us. "We do not know what we're seeing" does not equal "We're seeing alien spaceships."

Richard Pape from the University of Chicago's Project on Security and Threats, on what he's learned from studying the people arrested for the Trump Insurrection:

One overriding driver across all the three studies that we've now conducted is the fear of the Great Replacement. The Great Replacement is the idea that the rights of Hispanics and Blacks -- that is, the rights of minorities -- are outpacing the rights of whites. ... The number one risk factor [in whether a county sent an insurrectionist to Washington] is the percent decline of the non-Hispanic white population.

The whole interview is worth watching. The insurrectionists are overwhelmingly white and male. We ordinarily think of violent revolutionaries as young and desperate, but these folks are mostly middle-aged and well-to-do, with some of them owning their own businesses. What unites them is racial anxiety, their fear that whites are losing their superior place in American society.

Sean Hannity, who is worth $250 million and makes $40 million a year, advises his listeners to "work two jobs" rather than "rely on the government for anything". Better that you should never have time to see your kids than that he should have to pay taxes.

and let's close with something ridiculous

"One of the craziest, little-league type plays you'll ever see." Batting with a runner on second and two outs Thursday afternoon, Cub shortstop Javier Baez apparently grounds out to end the inning. When the throw from third pulls the first baseman Will Craig off the base, he moves to tag Baez, who starts retreating back towards home. Craig forgets he could just go back to tag first and end the inning, and things just get wilder from there.